Vision can be described in many ways. Too often, ‘vision’ is equated with ‘eyesight’. Eyesight is one important element of vision, but vision is a process that recruits and involves several other functional elements. To illustrate, a camera on its own may have many of the requisite elements to take pictures – but it cannot take pictures on its own.

In this brief article, I’ll break down elements of vision at a high level. To learn more, feel free to sign up for the much more detailed programming available through PESI.com – click here.

The camera in our example is akin to the eyeball itself: It is used to focus light by first directing it to the subject, focusing, maintaining stability. The camera has a sensor that picks up light information, the eye has a retina. If the camera is shooting RAW files, then the information requires further processing before it can be appreciated as an image. Likewise, while the retina does do some rudimentary image processing, it does not render the final the image, this is left primarily to the occipital cerebral cortex. Other parts of the brain and cortex chime in, allowing us to recognize objects and manipulate them mentally.

One obvious issue with the camera analogy is that, like the eyeball, there are other external mechanism required to direct gaze and attention, and to maintain that gaze through stabilization of the eyes in a moving head which moves in the environment.

In order to stabilize the image, we rely on two parallel sensory pathways: Somatosensory (touch/pressure/proprioception), and balance (vestibular function). The brain has several direct and indirect connections between eye muscles, balance (inner ear aka vestibulum), and proprioception. These are all mapped against a common ‘visual spatial mapping’ system, which has redundancy through the different mechanisms of touch and balance. For example, if you hear a startling noise over your right shoulder, mapping of auditory cues against knowledge of body position, head position, and position of the eyes in the sockets gives us the background information to immediately turn our heads and acquire the visual target, the source of the noise. Vestibular input allows us to accommodate for head movement and movement of the target in the environment to keep the image centred. We finish the picture with a mapping of space as two overlapping visual fields – the central fields (approximately only 3 degrees) being responsible for the detailed view of things, and the great majority of the rest categorized as peripheral visual fields which provides us directional guidance and a system for monitoring movement. The overlapping of the visual fields provides us with a sense of depth, or stereopsis.

It is sometimes heard these basic elements of vision described as a chair, so the ‘chair of vision’. Three legs, each roughly equivalent in importance in the active process of human vision; without one leg, the chair will topple:

- Ocular – Retinal (overlapping visual fields to create visual space), and positioning input through proprioceptors in extraocular muscles.

- Vestibular – information re: body movement to help understand movement on the retinal: Is the world / target moving or is the body / head movement.

- Somatosensory – how are the body and head positioned? This provides an understanding of how we should direct our gaze.

These three represent the core of human vision. The legs of the chair of vision are required to locate, acquire, and study visual signals (aka targets) of interest. The balance and health of the three legs will determine functional outcomes and impact on behaviour.

- Fourth leg: Auditory – as in the example above, auditory-spatial mapping of the world around us provides another target grid from which to launch head and eye movements to acquire targets. Since this pathway is complementary but not required, I typically don’t include it as part of the core visual system.

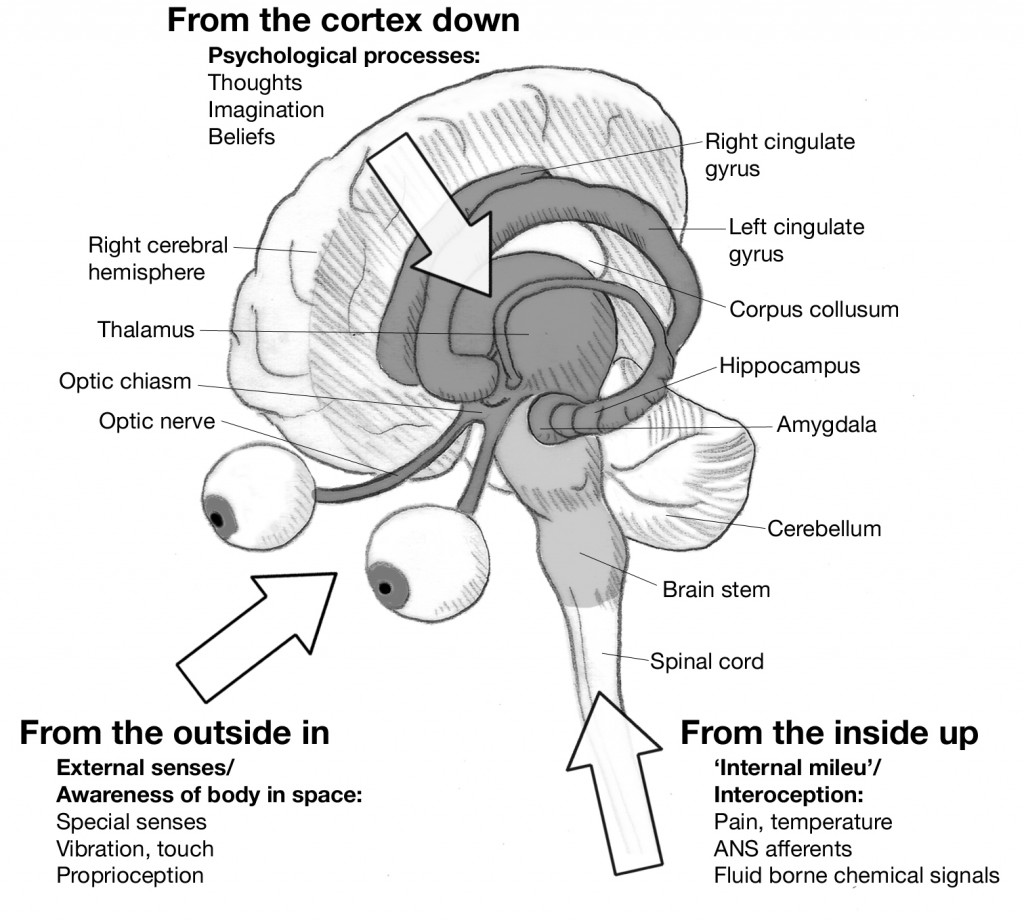

Given a strong foundation for visual exploration, it becomes useful. We can issue commands from higher cortical centres to direct gaze and study our environment, or objects of interest. Higher cognitive and motor functions, for example, rely heavily on visual input and fine control of visual processing and data collection. Likewise, many reflexes rely on accurate understanding of our positioning in space.

If the foundation is askew, everything built upon it, or all those functions that call upon it, will be negatively impacted. As a reader, for example, moderate astigmatism can impact upon how well we do, but so can a mild brain injury that has affected vestibular function. On the one hand, the image clarity is suboptimal, on the other hand, the eyes cannot stabilize a target on the retina to allow for study. In the case of reading, the precision of saccadic function is particularly important – something that is often affected by TBI/mTBI. There are likewise myriad concerns that can arise in each of the three vision pillars, both individually, and in combination one with the others.

Understanding visual process means to first look beyond visual acuity, the simple clarity of what is seen. Visual stress and dysfunction are not always related to clarity of the visual signal and are frequently a matter of something else, some other element in the chair of vision that is throwing things off. As a competent therapist, you should know what these elements are and learn to address those.

Vision is more than eyes.

Image from:

This is helpful