Subscribe to Vision Mechanic on YouTube.com

Subscribe to Vision Mechanic on YouTube.com

(The goal of VisionMechanic.net is to provide science-based clinically relevant resources about humans, for humans. All humans. This series highlighting International Vision and Learning Month (August) is more focused on those humans who are in formal learning programs, most notably, younger humans. If you yourself are a learner, or if you teach them, guide them, care for them or provide therapy for them, then this series will be of interest to you.)

Think about this for a few moments: How often do you move your eyes? Even as you’re reading this, or driving down the road – how many times per second are your eyes darting here or there, how long do they sit on one target in particular? We don’t simply spend our time looking straight ahead and we don’t spend our days turning our heads to find new targets – that would be a burden that would surely stop us in our tracks. Instead, we turn our eyes to locate targets because it’s much faster, much more energy efficient – and it allows us to take in the maximum amount of information with quick snapshots of hundreds of unique targets every single minute of the waking day. Were we to suddenly rely on our necks to move our eyes, human activity would grind to a virtual halt.

…these metrics, like others mentioned in this series (even so basic as refractive state), are virtually never considered when children are referred for standard pediatric assessment of behaviour and learning/reading concerns – even though they are known to have significant impact on child learning, development, and behaviour.

You’ll understand more after reading this brief outline of the different kinds of eye movements we rely upon – but never even think about. We’ll consider very briefly how these can affect child development and behaviour. Bear in mind as you read that these metrics, like others mentioned in this series (even so basic as refractive state), are virtually never considered when children are referred for standard pediatric assessment of behaviour and learning/reading concerns – even though they are known to have significant impact on child learning, development, and behaviour. This represents a major failing in professional colleges in education, psychology, and medicine/pediatrics.

Start with this, a simple experiment: Try to not move your eyes. If you need to see something, or scan text for example, try to only move your head while keep your eyes pointing straight ahead. You’ll soon find this impossible to do for any period of time.

Step 2: Hold your head perfectly steady and continue reading. Pay attention to how many very small eye movements you are making. Now look straight ahead and while holding your head still, practice moving your eyes to different targets in all extremes of your visible field of view. Notice how much easier it is to do this rather than to move your head to accomplish the same task.

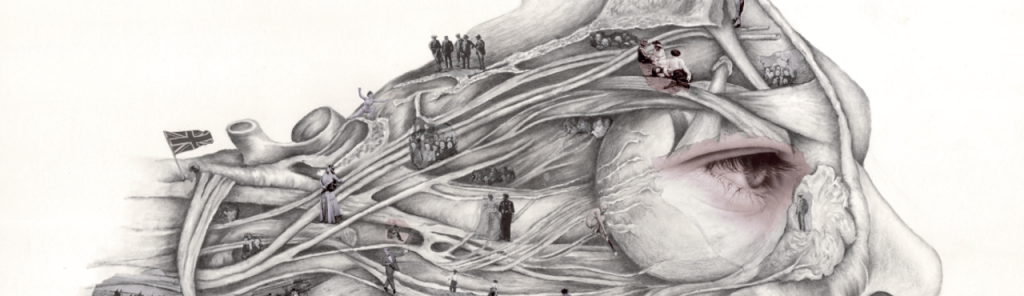

Click the link or the picture to learn more about how are visual systems have layers of complexity. A great part of the visual system, about half of it, is geared towards targeting objects and moving the eyes.

The above graphic is one of many in the collection ‘Art of Eyes‘, a series of detailed and imaginative illustrations about the human eye and all that supports it. Partly pictured here are some of the pieces of the eye movement system. The nerve networks, muscles, and muscle sensors that are responsible for moving the eyes and holding the eyes in place are complex, no less complex than the nerve tissue and brain connections that capture light and turn it into a usable signal we call ‘sight’.

Muscle movements of the eyes can be broadly classified as follows. Obviously the details are a whole lot more … detailed, so refer to Adler’s Physiology of the Eye, or Principles of Neural Science, or Neurology of Eye Movements for more.:

- Fixations: Holding a target steady. This is actually maintained by a series of minute movements that we do not perceive. When we think we are holding fast on a single target, the reality is the eye is making countless micro-movements to keep the target freshened on the retinal receptors, and for other reasons. Fixations allow us to verify targets and to study them in more detail. Fixations develop relatively early in life.

- Pursuits: Smooth targeting of targets like birds in the sky. This sort of smooth tracking is only rarely used in daily life for most people, that is, relative to other forms of eye movements. Pursuits take a little longer to develop and, like other eye movements, become stronger and more accurate with use. Pursuits have an important role to play in maintaining balance (and helping to avoid nausea) when we are moving and objects around us are also moving.

- Saccades (pronounced ‘suh-kades’ or ‘suh-kawds’): Next to fixations, saccades are our most important type of eye movement. When we are young, we move our bodies and heads to find targets. In time, we learn to do ‘short hand’ by moving the eyes instead – this saves time and energy, a lot of energy. Speed and accuracy comes with practice with moving in the environment and interacting with objects in it. Saccades also become more refined with an evolving brain and mind and are driven by attention. Jumping from one visual target to another with quick and easy accuracy is the foundation to reading – so much so that you can predict a child’s reading outcomes by assessing saccadic skills alone. Thankfully, these skills like other visual motor skills can be trained. Aside: One of the first things to suffer after a concussion is saccadic function.

- Vergence: Technically, vergence is the ‘opposing movement of the eyes’, so eyes moving in opposite directions to one another. There are two examples of this – crossing the eyes inwardly (convergence), and moving them outwardly away from the nose (divergence). Both eyes must maintain contact with the target at all distances, and so vergence is important for many reasons and will be the foundation for all other types of eye movements. When convergence fails, children feel this as strain when reading – the eyes struggle to pull inwardly, so muscle strain and double vision. This condition is associated with ADHD and reading concerns. When the eyes struggle to diverge, distant objects can appear doubled or blurry. Sticky vergence (reduced vergence range and facility) can also lead to difficulties targeting targets near then far, or far then near – so copying from a board will be difficult. Again, like other visual motor skills, vergence can be trained. Like saccades, vergence is often affected after stroke and this causes trouble with near work, like on computer screens.

- (Accommodation: This is another muscle ‘movement’ of the eye but it’s invisible – accommodation is the action of the ciliary body to change the shape of the lens to focus light. So, it’s a movement that can affect other eye movements, but does not itself move the eyeball. Reduced range and ease of accommodation is often associated with reading trouble, or after a concussion.)

The experts out there will complain that I’m leaving out a million things, but that’s fine. The goal of this series is to underline and highlight common elements that commonly contribute to learning and developmental concerns. You can always find more in books like the wonderful Adler’s Physiology of the Eye, or Neurology of Eye Movements. Or, for when things go awry, Eye Movement Disorders (among others).

… all chairs need at least three legs, and accurate visual targeting requires vision/sight, balance, and body sense to be in proper working order.

Things get even more complicated when you consider there are two other main inputs to targeting, other than vision, that is: Balance (what is known as vestibular sense) and Body Sense (aka somatosensation). When either of these is troubled or burdened by illness or developmental trouble, visual targeting will be affected – all chairs need at least three legs, and accurate visual targeting requires vision/sight, balance, and body sense to be in proper working order.

Finally, to really complicate things: All these muscle actions can be controlled voluntarily by learning and through experience, and they can also be activated by reflexes. Sometimes these can come into conflict in some interesting ways – like when you feel you’re moving at a stop light when it’s really the car beside you that’s moving. (See Vestibulo-ocular Reflex and Optokinetic Reflex)

Have a look at this post to learn how to assess ocular motor skills

Expand your understanding:

- Get a head start by having a look at other posts here at visionmechanic.net, or on the Vision Mechanic YouTube channel.

- Learn more in a more formal way, consider taking one of the growing number of professional credit VisionMechanic.net courses for developmental professionals (teachers, doctors, therapists, psychologists).

- Join the Vision Rehabilitation Group on FaceBook.

One Response